Memoirs of a Former Dick-Panderer

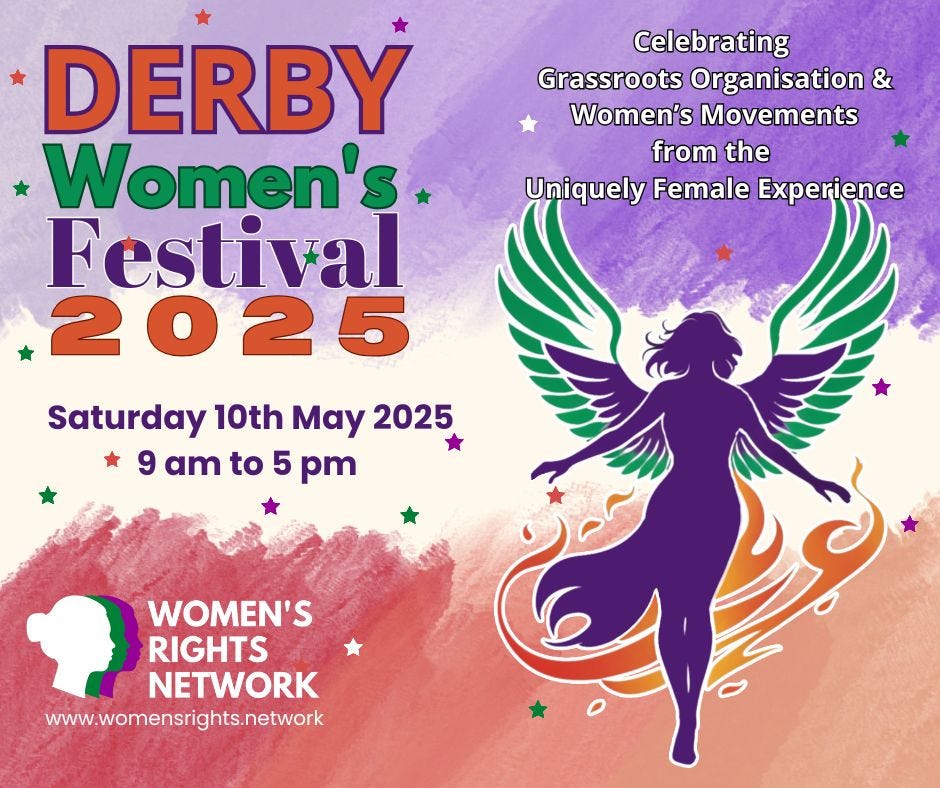

What follows is the speech I gave to members of the Women’s Rights Network in Derby on Saturday, 10 May 2025. Thank you to all the women who made the event such a success.

Fifteen years ago, when I founded the local activist group Chelt Fems, I was a total dick-panderer. There wasn’t a furrowed male brow I wouldn’t rush to soothe, nor an unsupported bollock I wouldn’t eagerly cup. And what’s truly mortifying is that I called myself a feminist while doing it. Somehow, I had convinced myself that feminism meant being nice — to everyone. Especially men. That the best way to achieve change was to be as inclusive and intersectional as possible.

It’s only now, with a decade’s distance, that I can see how warped my values were — and how stereotypically ‘feminine’ my behaviour was, even as I insisted I was fighting stereotypes.

So today, I don’t just want to talk about how campaigning can change the world.

I want to talk about how it changes you.

I also want to make a controversial point: I believe radical feminism is elitist—not in privilege, but in principle. It demands clarity, courage, and rigour. And that’s a good thing.

To be honest, I’m out of my comfort zone here. I don’t like speaking about personal experience. But as I’ve been asked to, I’ll tell you a bit about my background.

As an embarrassingly middle-class young woman from the leafy Cotswold town of Cheltenham, I was always an oddity.

At the time my peers were packing their rucksacks for gap years and heading off to uni, I had no qualifications and was busy dropping out — living with a string of useless men and immersing myself in conspiracy theories about chemtrails and the perils of fluoridated water.

I gravitated towards far-left politics: direct actions at airbases & Mayday protests.

At the time, this was fairly niche and I became used to championing unpopular causes & trying to make the disengaged majority care.

Ironically, twenty years on, some of the apolitical friends who sneered at me as they were getting their marketing degrees now spend their days on social media regurgitating half-arsed Marxist slogans and berating ‘TERFs.’

All of this is to say: what drew me to feminism wasn’t deep dive into Dworkin.

It was vague anti-establishment instincts, to which “men and women should be equal” seemed a natural bolt-on. It took years to realise that sexual politics wasn’t just a subset of leftism — it was a political movement of its own that cuts through every aspect of life.

I set up Chelt Fems after watching similar groups forming in Bristol.

I went to workshops on activism and making zines.

I drank in their messages about having a wide appeal, being democratic, centring ‘minoritised voices’. The group was open to men — which, in hindsight, neutered it from the start.

At the time, I was also a women’s officer at the union of a social housing provider. I applied the earnest ideas from the Labour movement— ideas which, on reflection, were alienating and irrelevant to both the female-dominated workplace and Chelt Fems.

Still, I headed up some campaigns I'm proud of: we fought against the council licencing lap-dancing clubs, against sexist stereotyping in children's books and for the closure of Yarl's Wood detention centre.

Those fights are ongoing — which some might see as failure. But the consciousness-raising, the skills we learned— they created ripples. And I believe these fed into the terf tide which has since swept across the UK. It was during my time as chair that I peaked thanks to brave, and gloriously gobby women.

To backtrack: I launched the Chelt Fems by slipping bookmarks into feminist books at the local library, pretending there was already a thriving group, and asking a feminist speaker at the Cheltenham Literature Festival to give us a shoutout. I set up a Facebook group and soon people started getting in touch.

After a couple of years of meeting and campaigning something shifted. I was approaching thirty, and most of the active members had been a little older. Suddenly, we started attracting younger people in their late teens and early twenties. On reflection, this was because of the rise of zombie feminism.

By zombie feminism, I mean that brain-sucking movement that reduced centuries of feminist thought to t-shirt slogans like ‘Smash the Patriarchy’ and endless awareness-raising hashtags.

Until then, I’d never been a part of a popular campaign & Cheltenham was a ‘small c’ conservative stronghold. So when crowds turned up for our feminist hustings and rape crisis fundraising gigs, I was baffled but quite excited.

I hated the idea of being a figurehead and was so shy I would do as much as I could via email to avoid having to meet any local politicians or policy makers.

But I began enjoying blogging. At the time the local paper was looking for content, and a friend in the group encouraged me to give it a go. I ended up writing a short regular column. It provoked strong opinions and did quite well.

On a personal level, it did me a lot of good. Because I was absolutely sure of the truth of what I was writing, because I was passionate, I stopped caring what people thought.

I felt like I was channelling something bigger than me — and my confidence grew. I learned to cope with backlash.

Ultimately, that's how I ended up in journalism. I had no idea I had any aptitude for writing before then.

Despite the group’s growth, I clung to my naïve ideals: endless discussions on the most basic of points of feminism to try to get everyone up to speed, vegan catering at meetings, spending my own money hiring venues to avoid potentially excluding people by meeting in a pub. But when it came to doing the real work — writing to local councillors, slogging through paperwork — it was always the same tiny handful (most often me and my girlfriend, who’s now my civil partner).

I started noticing patterns: how our so-called male allies had a knack for taking centre-stage, how they never acknowledged their blindspots or weaknesses. I noticed how, in mixed company, women apologised before speaking, deferred when interrupted, and softened their anger. I learned from the older women.

And I noticed something harder to admit: how often women policed each other — viciously. I was constantly pecked at and undermined — often by women who contributed nothing themselves. I realised it was jealously and that many women, even feminists, try to take down those with the temerity to speak out.

In short, I started to really notice sexual politics.

(As a side note, that's when I vowed: never criticise a fellow activist unless I’m doing something better myself. I sometimes fail but I really think not picking on other women is one of the most radical things you can do.)

Anyway, there was one moment which crystallised everything. Sitting in the flat I shared with my partner, a young man, a student — who had accompanied his largely silent girlfriend —took a red pen to a position paper I'd written opposing the sex industry. Leaning back comfortably on our sofa, he scrawled notes all over my paper with comments like: "all work is exploitative — why is selling sex any different to waiting tables?"

I didn’t say anything at the time. But inside me, something snapped.

I did the most British passive-aggressive thing ever; I wrote a furious blog about the entitled behaviour of some men in the group using him as an example. I didn’t hold back.

Predictably he read it. He was furious and the group started to shed members who were offended by my ‘misandry’. Others cheered. It was like turning on the lights and watching cockroaches scatter.

And I realised: I didn’t care about offending fools, and I started to recognise that being hated by dimwitted prats was a sign I was doing something right.

Until then, I had clung to the belief that we had to work with men to get anywhere. I even pitied them, convinced they too were trapped by gender norms. I wasted hours explaining why male strippers at hen parties were bad, but not the same as the global trafficking of women for sex, and how ‘slut walks’ and ‘free the nipple’ stunts might actually set us back. I tried to articulate why feminism was not about equality, but about liberation.

But the more I watched the so-called good guys—the self-declared ‘male feminists’—the clearer it became: they had zero interest in examining their own power, let alone relinquishing it. And nor had the women who craved their attention more than self-respect.

So I stopped being kind and I started saying what I thought. I unlearned the rules of femininity & began to break free. I no longer cared if I was liked. It felt, and still feels, amazing.

Running Chelt Fems taught me to reject everything I had been taught by liberal feminism and unions about making political change. Of course, you have to find what works for you, but this is what worked for me.

Don’t be democratic. Be brutal. Put people in boxes according to their skills.

Approach your enemies with an open mind and your allies with suspicion.

Don’t try to appeal to everyone. Meet with anyone who might be useful & refuse to be shamed. Don’t try to include everyone. If people don’t like your methods they’re free to piss off and campaign in a way that suits them.

And here’s the central, uncomfortable truth I learned: while feminism might benefit all women, only some women — the smart and courageous ones — have the grit to really recognise and push against male oppression. These are the only elite worthy of your consideration. So, don’t blunt your activism by pandering to the thick, lazy or cowardly; be unashamedly elitist and find like-minded, brave women. They are out there- we’ve a hall here full of them.

Chelt Fems eventually became a casualty of the TERF wars. Though I passed it on in 2016 when I moved out of the town, it became inactive shortly after a disruptive ‘intersectional feminist’ university lecturer joined and started calling everything ‘problematic.’

After that, in 2017 I set up a short-lived group called Critical Sisters with an ex-Muslim friend, challenging groupthink on the left. We focused on the blind spots around misogynistic man-made beliefs like transgenderism and Islam. It was one of the first of the new wave of sex realist groups.

Then I launched an anti-porn group, which sadly folded during Covid.

During this time, I experienced trashing from fellow feminists when I organised a conference. Activism has given me a thick skin, but what women put me through cut more deeply than anything a men’s rights activist could’ve thrown at me.

I was a witch again, only this time those lighting the taper were women I had once respected. My partner made me promise never to organise another feminist event again. And I haven’t. But now I’ve come to feel grateful to the women who bullied me.

Because thanks to them today I do a more selfish form of activism: campaigning journalism.

For much of my time running groups I honed my writing skills through blogs and letters. In 2020, I switched to journalism full time.

I’m far better at writing than I ever was at campaigning — but I would never have found my voice without grassroots feminism.

If I have one regret, it’s that I spent too long trying to make feminism palatable to the very people it inconveniences.

Now, I’m done cushioning egos and I’ve dropped the ball palming.

And I’m finished apologising — to anyone — for being good at what I do.

Instead, I stand — stubbornly, unapologetically — alongside my sisters. Even the ones I can’t bloody stand.

And frankly, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be. Thank you.

We have much in common. I've been organizing radfems online and off since 2005 when I started the forum at Genderberg, led several feminist groups in Portland which I had to abandon for similar reasons as you, and also continued my writing career.

I'm a founder of WoLF (Women's Liberation Front). When you wrote, "Put people in boxes according to their skills" it painfully reminded me of an early 2013 meeting where I suggested we ask WoLF volunteers to share what skills they have- any skills they have -so we could plan how best to take actions.

My suggestion made me evil according to a detransitioned woman on WoLF's first organizing committee. She accused me of coldhearted, ruthless use of skilled volunteers (we never collected the list of skills), and berated me as a terrible feminist with, "What about women who don't have any skills? Why don't you care about them!?"

It's not a pleasant memory, but it's one I'd forgotten and I appreciate you reminding me of it. Thanks as well for braving the topic of how challenging on multiple levels feminist organizing has been these past twenty years. The full story of how WoLF came into existence would paint an intriguing and not very flattering portrait of modern feminist organizing.

Listening to people smugly rationalize and justify modern internet "porn" has morphed into realizing that yes, there is a problem with young men being angry and misogynist and yes, young women are depressed and anxious - yet they refuse to connect the two things. Insane.